.jpg?width=750&name=shutterstock_1691767204%20(1).jpg)

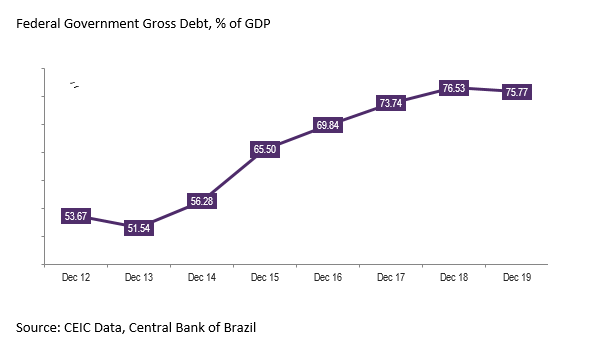

Brazil’s gross public debt reached a record high level of 78.99% of GDP in July 2019, following an upward trend that started back in 2014 due to fiscal imbalances, as public expenditures began to grow more than revenues, in primary terms.

In December 2019, the figure slipped to 75.77% of GDP thanks to the government’s efforts to improve fiscal sustainability.

However, it might be still too early to claim that a public debt reduction trend has been established and it would take persistence and consistency of reforms to ensure control of public spending and debt stabilisation.

Brazil’s gross debt climbed from 51.5% of GDP in 2013 to 76.5% in 2018. The bulk, over 90%, of this increase, was accrued interest, because the government repays old debt and interest by issuing new debt. Prior to 2014, Brazil frequently reported primary surplus. However, in 2014, public expenditures began to grow faster than revenues, leading to primary deficit, accelerating debt growth. The increased risk of government bonds pushed up interest rates, which soon impacted accrued interest, as 39% of the public debt had a maturity less than one year in December 2014, and were renewed with an increasing yield. The economic recession, which reduced tax revenues and the GDP, also contributed to the higher debt-to GDP ratio between 2014 and 2018. On the other hand, currency fluctuation had a limited impact on debt, as more than 93% of the debt in the period was in national currency.

In the second half of 2019 the effort of the Brazilian economic team, led by economy minister Paulo Guedes, finally started to bear fruit. In October 2019, the Senate gave the final green light to the pension reform, aimed at aligning the growth trend in social security expenditures with the GDP growth rate, and generating savings for the central government of around USD 182bn in the next ten years.

Prior to this approval, as the pension reform was making its way through Congress and in line with its potential impact, on July 31, 2019 the Brazilian central bank decided to start cutting the Selic benchmark interest rate, which had been stable at a level of 6.5% during the previous 16 months. According to the central bank’s statement, “the pension reform, by adapting retirement rules to the country's demographic structure and dynamics, slows the pace of government spending growth”. Also, it “reduces the risk premium component of the structural rate, as the reform improves the prospects for fiscal sustainability.”

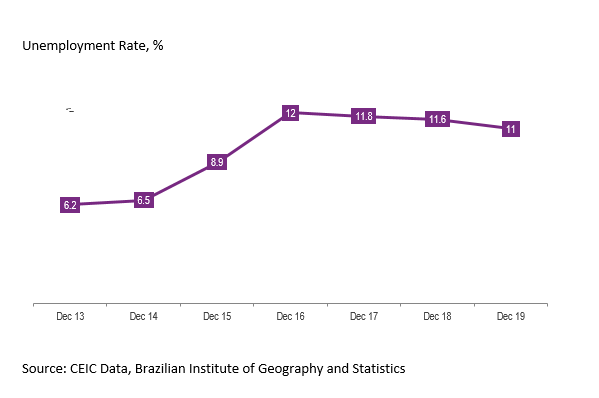

Since then, the central bank has cut the Selic rate multiple times to 4.25% as of February 2020, driven by weak inflation and the slow reaction of the economy to the previous cuts. In the second half of 2019, the recovery remained weak, with the central bank’s economic activity index still not on a clear growth path. Capacity utilisation in manufacturing has remained firmly below 78.5% since June 2015, and the unemployment rate was over 11%, still above the 7% average observed between 2012 and 2014, before the 2015-2016 domestic crisis.

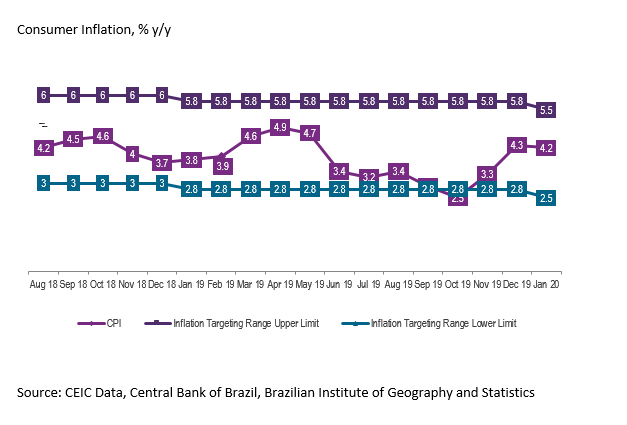

The low inflation reflected the subdued domestic demand. The official consumer price index (IPCA) varied close to the lower limit of the target range (2.75% - 5.75% y/y) during most of the second half of 2019, falling as low as 2.54% in October.

The continuation of this scenario in 2020 prompted the central bank to further cut the Selic rate to a record low of 4.25% on February 5, 2020. The monetary policy committee Copom signalled that it will most probably remain cautious during its next meeting due to the “lagged effects of the monetary easing cycle that began in July 2019.” The committee’s next steps will continue to depend on the economic activity, the balance of risks, and inflation projections and expectations, with increasing weight for 2021.

Just as the Selic rate, the 10-year government bond yield is also at a record low level, reflecting the lower default risk of the Brazil’s public sector. It reached 6.22% in November 4, 2019, a four-year low, and as of February 20, 2020, it was 6.37%. As a consequence, the federal government’s interest expenses, accumulated in 12 months, dropped to 5% of GDP in June 2019, the lowest levels in five years.

The meaning beyond the numbers

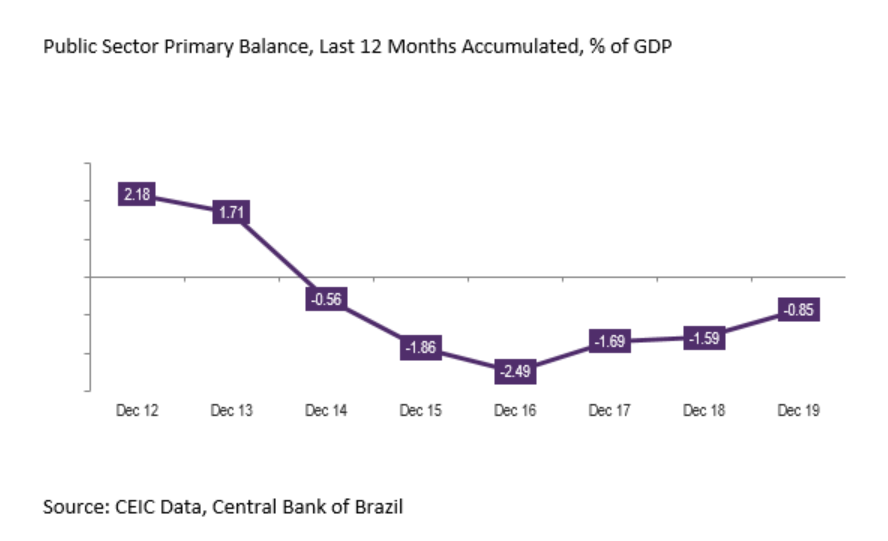

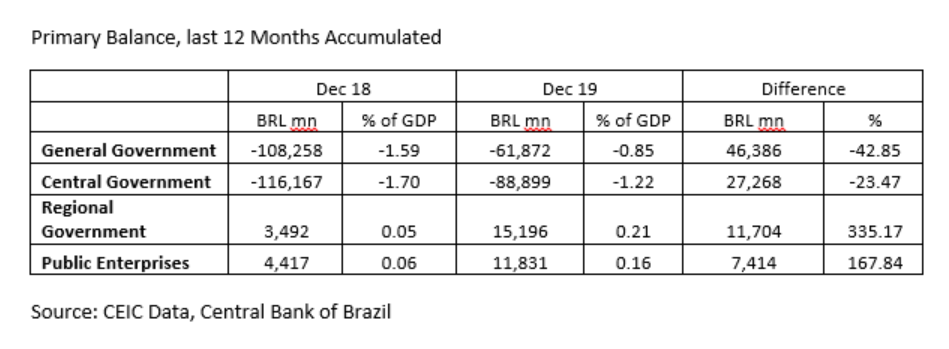

In 2019 the federal government’s primary deficit fell to 0.85% of GDP or BRL 61.8bn, the lowest figure since December 2014, before the domestic economic crisis.

Although the central government accounted for more than half of the general government deficit reduction (BRL 27.3bn out of BRL 46.4bn), proportionally, regional governments and public enterprises have actually made greater efforts to expand their surpluses.

Regional governments, for instance, saved 335% more in 2019 compared to 2018, while public enterprises increased their surplus by 167.9%. The decrease of BRL 27.3bn in central government’s primary deficit in 2019 was largely a consequence of the payment of BRL 34.2bn from Petrobras for buying 90% of the oil fields sold in the oil auctions round of November 2019. The deficit was not reduced by the same amount in part because mandatory expenses, like social security and labour costs, continued to grow, but also because discretionary expenses also grew above the 2018 figure, especially in the end of the year. Without the extra revenues from Petrobras, the central government’s primary deficit in 2019 would have been actually bigger than in 2018, according to the Observatory of Fiscal Policy, maintained by the Getulio Vargas Foundation, a renowned Brazilian research institute.

Apart from the payment by Petrobras, the central government also received two other extraordinary cash boosts in 2019 – BRL 137.7bn (USD 36.9bn) raised by selling international reserves and a BRL 100bn early debt repayment from the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). These are financial revenues, not considered in the calculation of the primary deficit, but used to decrease the federal government’s gross debt.

According to the Institution of Fiscal Studies (IFI) of the Brazilian Senate, without the earlier debt repayment by BNDES to the Treasury, the general government’s gross debt would have been 83% of GDP in November 2019, which means that it would have continued to grow.

The IFI also estimates that the sale of international reserves by the central bank reduced the share of the gross public debt by 1.6 pp of GDP. The central bank decided to change its strategy to trade foreign currency on financial markets, relying less on foreign exchange swaps and more on selling actual US dollars, reducing international reserves. In such operation, the government exchanges foreign currency for BRL. To avoid a monetary contraction, which could raise interest rates and hamper the expansionary monetary policy, the central bank redeems bonds from repurchase agreements (repos), which means repaying them at or before maturity date. Thus the central bank is putting money back in circulation and the final effect is a reduction of the gross debt...

Sign in to read the full article here. It may also interest you to learn more about the CEIC Brazil Premium Database - the definitive go-to resource for analysts, investors, and strategists to assess and run analytical models on Brazil's economy.

.png?width=160&name=ceic-logo-Vector%20logo%20no%20tagline%20(002).png)