The October data for China’s new loan prime rate (LPR) has remained unchanged from September, suggesting that the government’s goal to align the official lending rates in China with the market–driven ones may not be achieved easily.

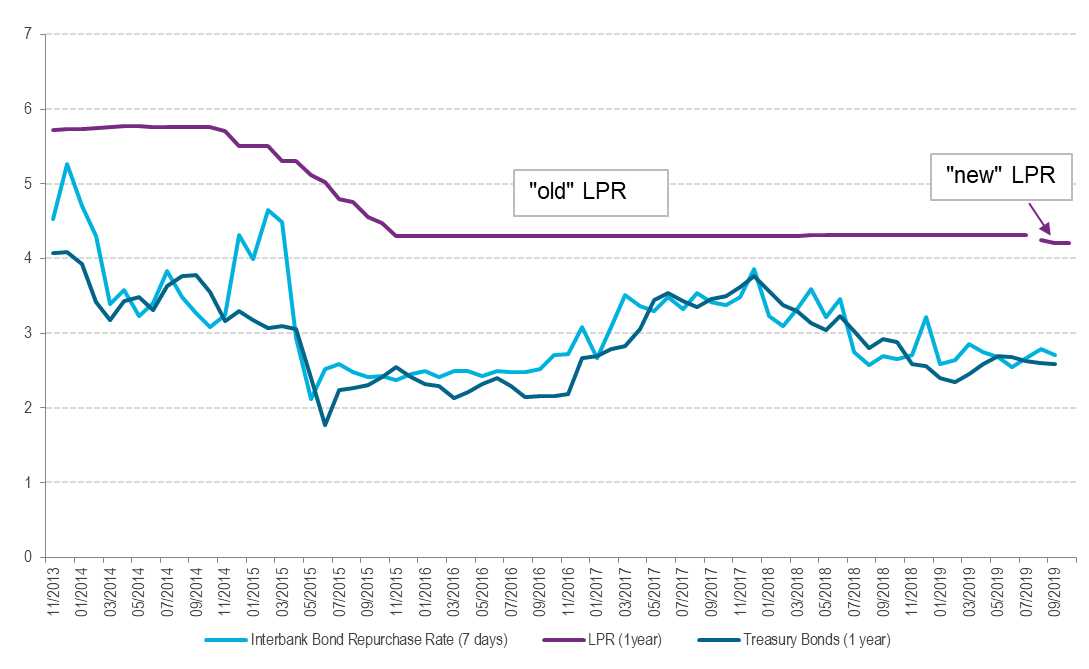

This was the third monthly data release since the new LPR was introduced in August as part of the broader government effort to liberalise interest rates in the country. In line with the government’s goal, the new LPR was going down in the first two months, from 4.3% for one-year loans, a level at which the old LPR had been since October 2015, to 4.25% in August 2019 and 4.2% in September 2019. However, in October 2019 the rate remained unchanged at 4.2%. The rates on five-year loans remained stable at 4.85% in the three months after the launch of the reform.

While three months is too short a period for drawing conclusions, the flat rate in October is a signal that the effect of the reform may take time and the two-month decline of the LPR was just an initial short-term effect, while the structural problems of China’s banking system would make the goals of the reform harder to be achieved. The banks may remain unwilling to lower interest rates on loans for private small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with higher risk exposure. Also, the unchanged rate in October reflects the surge in pork prices in September and the central bank’s attempt to keep the inflation stable in the short run.

Loan Prime Rate and Market-Driven Interest Rates

Source: National Interbank Funding Center, China Central Depository & Clearing Co, CEIC

The LPR reform introduced by China’s central bank in August has become a controversial topic for discussion with opinions ranging from considering it a tool to cut interest rates to believing it is a measure with ambiguous effect. There is, however, no doubt that the short-term effects of the reform are part of the Chinese government’s toolbox to soften the economic slowdown and the impact of the trade wars on the economy by redistributing funds from banks to the real sector, while at the same time it is another step towards a market-driven interest rate.

China’s efforts to liberalise the interest rates in the country date back to 1996 when the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) started to gradually increase the upper limit of the lending rates until October 2004 when the ceiling was removed, while in July 2013 the central bank declared full liberalisation of the lending rate by removing its floor as well. In October 2013, the Chinese central bank initially created the old LPR as a lending rate that the commercial banks used for loans to their best clients. The rate was designed to better reflect the market demand for funds than the PBoC benchmark. The lower band of mortgage loan rates, on the other hand, has been lowered in two occasions in August 2006 and October 2008.

However, despite the government's efforts, the LPR dynamics have remained far from those of the market-driven rates, restricting the central bank's ability to transmit its monetary policy to the real sector. Commercial banks remained reluctant to reduce their profits by lending at market-driven interest rates and continued to price loans not much lower than the central bank's benchmark lending rate. Under the new mechanism, the LRP pricing would be linked to the rates of the PBoC's medium-term lending facility (MLF), a funding facility of the central bank to commercial banks. The MLF rate better reflects the liquidity demand of the broader financial system, and at the time of announcing the reform in August, the central bank's one-year benchmark interest rate was 4.35%, while the MLF rate stood around 3.3%.

Besides lowering the lending rates, which is vital for stimulating the economic growth, linking the LPR to the MLF rate would help transpose the central bank's monetary policy to the whole financial system and the real economy by making the lending rates offered by commercial banks more sensitive to the changes in monetary policy rates. Moreover, the new LPR is expected to cover more lending to small and medium enterprises (SME), mostly private ones, which is another goal of the reform. According to the methodology for calculating the new LPR, the number of banks quotation's contributing financial institutions is extended from ten to 18. The newly added institutions include two foreign banks, two private, two urban and two rural banks, all of them providing loans mainly to private SMEs, rather than to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Also, the PBoC changed the methodology for calculating the LPR from weighted average to simple average, thus giving the quotations of the newly added smaller, banks in the pool equal the same weight as those of the large state-owned banks.

Source: National Interbank Funding Center, CEIC

Put in the broader perspective of the current state of the Chinese economy, the LPR reform is more than just an attempt to speed up the interest rate liberalisation and decrease the interest rates in the country. In fact, giving more freedom to the interest rates and letting them fluctuate with the market would bring them up when the business cycle reverses. The secondary, and probably more substantial, expected effect of the reform is the resource redistribution from the speculation-prone financial and real estate sector to more sustainable sectors in industry and services. With the long-standing concerns that China's financial sector could be a ticking bomb that is about to explode, the interest rate reform is a part of Beijing's effort to curb the investment boom in the housing market.

A key part of the interest rate reform was the differentiation between the maturity terms of the LPR for mortgage and lending rates. With the new methodology, the interest rates on mortgages are linked with the five-year maturity LPR based on the same calculation methodology as the lending rate. The differentiation of the LPR terms will allow the central bank to more easily apply different policy targets to the short-term business loans and long-term housing loans.

However, the real success of the LPR reform depends on the successful implementation of other structural changes such as developing an efficient fund transfer pricing system for commercial banks, competitive neutrality for the SOEs and efficient bankruptcy legislation, to name but a few. Otherwise, the reform will achieve its goals only partially, with a limited effect on the economy.

View our full normalised data on China that you can use for comparison and analysis of various economic factors

.png?width=160&name=ceic-logo-Vector%20logo%20no%20tagline%20(002).png)