In the shadow of a fierce trade war between the world's two largest economies, never-ending negotiations over Brexit and increasing geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East, the world is preparing for the first synchronised economic slowdown since the end of the global financial crisis in 2009.

While the economic data for the major economies since the beginning of the year has been highly volatile and mainly driven by the news, there have been clear signals that the expansionary cycle stage in the United States and other advanced economies is coming to an end. Various leading indicators from the real and the financial sectors have shown early signs of the looming downturn. In the second half of the year, the purchasing managers' indices (PMI) in the advanced economies declined substantially, forecasting gloomy economic sentiment in those countries. Industrial production growth has consistently decelerated, reaching negative values in most advanced countries, including the United States, Japan and Germany – the single growth engine of the stagnating eurozone economy.

The automotive market in the US is in decline with negative annual growth of motor vehicle sales in eight of the first nine months of 2019. While these indicators are highly dependent on trade and thus volatile to the dynamics of the US–China trade dispute, the signals from the financial markets are even more worrisome. In August 2019, the spread between the long-term and the short-term interest rates in the US turned to negative for the first time since late-2006 – a signal from the financial markets, known as an inverted yield curve, that has successfully predicted the past few recessions.

Timing, duration and magnitude of the business cycle stages are hard to anticipate. What is certain is that the expansionary period that followed the 2009 recession was weaker than the previous one. In order to boost growth, policy-makers around the globe have rolled out stimulus packages previously unseen in peacetime, pushing monetary and fiscal policies to their limits. Interest rates in advanced economies hit the zero-lower boundary in 2009-2010 and have remained at that level since. Money supply has sky-rocketed, mutating from a stimulus programme aimed at combating the recession and avoiding a 1930s-style depression to an open-ended policy of the Central Banks that lasted longer than anyone could have anticipated. Backed by the massive money supply increase, fiscal deficits have become the new normal for the advanced economies and government debt has reached record-high levels. Despite massive support from both Central Banks and governments, the post-crisis growth has remained uneven and fragile.

The US has enjoyed one of the longest expansionary phases in the history of its business cycles, but the uptrend was highly unsustainable, driven mainly by the accommodative monetary and fiscal policies and the wealth effect of the soaring stock market. Even with these drivers in place, the performance of the US economy has remained far below that of the preceding "boom" stages.

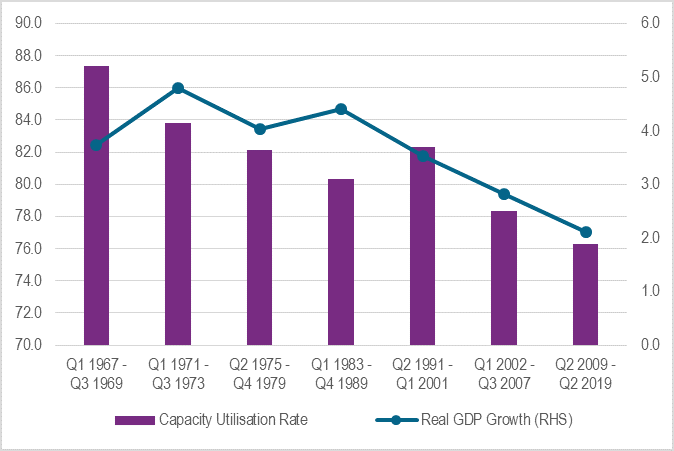

US Capacity Utilisation Rate and Real GDP Growth

Source: The Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Board, CEIC *Annual average

GDP growth in the US averaged 2.1% per year during the Q2 2009 – Q2 2019 period, 2.8% in the pre-crisis expansionary period (Q1 2002 – Q3 2007) and 3.5% in the decade that preceded the "dotcom" bubble burst (Q2 1991 – Q1 2001). Capacity utilisation also didn't reach the levels of the previous expansion periods. In Europe, the debt crisis in the Southern countries plunged the eurozone economy into a double-dip recession in 2011, while the Japanese economy didn't recover from its long-standing depression, even with the aggressive monetary and fiscal interventions under the Abenomics programme.

All this suggests that the period following the 2008-2009 crisis could hardly be called a "boom". Instead, this period looks more like a fragile recovery that will last until the cycle reverses again and the global economy heads back into a downturn. Moreover, the historical data shows that the latest expansionary period in the United States is not only weaker compared to the previous few, but the tendency of having weaker and weaker "boom" cycle stages started a few decades ago. In other words, we may be living in a world when the previously typical "boom-bust" cycle has been replaced by a "recession-recovery" cycle, where economic downturns are followed by periods of sluggish recovery.

Remembering the Great Moderation

What has made the recent expansions so weak? The modern economic theory gives a central role to the conventional monetary policy to combat economic downturns on the one hand and to cool down inflation on the other. This policy concept has been fundamental to the era known as the Great Moderation – a period of low economic fluctuations and stable inflation in the US and the rest of the industrialised world starting in the early-1980s. However, the situation has changed. No matter how generous the monetary policy stimuli have been, aggregate demand has remained insufficient and heavily reliant on fiscal spending. What makes the recent expansion different from the previous few is the enormously high amount of savings that could not be absorbed by private investment, as happened in the previous expansion periods in recent US economic history. While absorbing the excess saving via fiscal deficits during a downturn is a conventional anticyclical fiscal policy, doing so during a "boom" period is a sign of a structural change in the economy in which monetary policy is not enough to stimulate private investment.

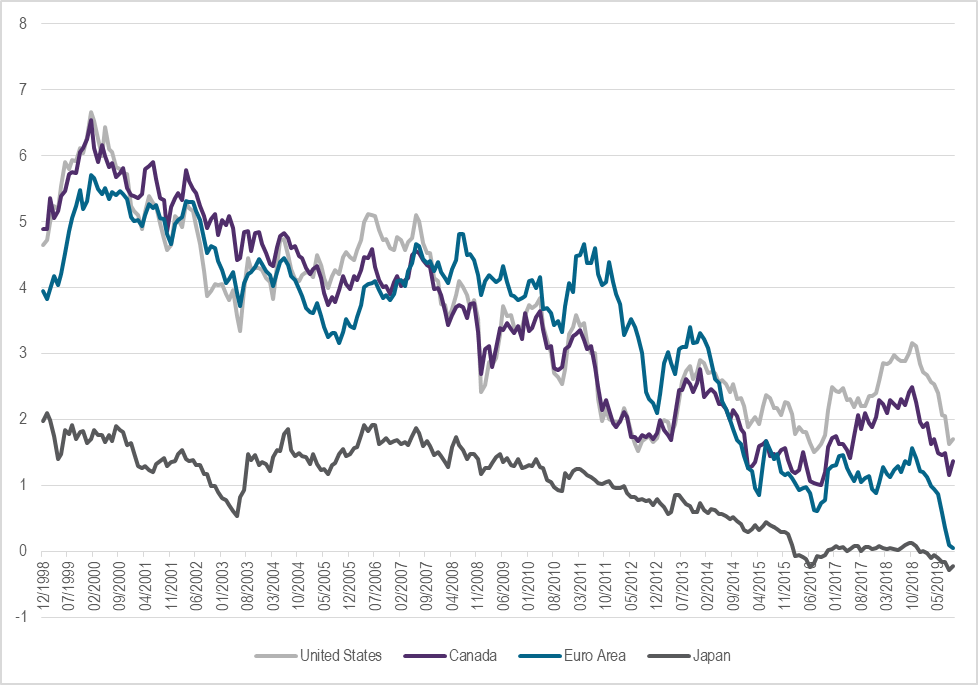

Over-saving was also the main cause behind another phenomena observed today – the record low interest rates that have persisted during the entire recovery period since the end of the global financial crisis. While the near-zero interest rates since the end of the recession came as a result of the Central Banks' expansionary monetary policy, the downward trend started more than 30 years ago.

Real Interest Rates in Advanced Economies, % pa

Source: Central Banks, Statistics Offices, CEIC

Constrained by the zero-lower bound, interest rates cannot be further decreased to a level low enough to stimulate private investment and absorb the over-saving – a condition of the economy described by the former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers as secular stagnation. A combination of various factors from both the demand and the supply sides have put downward pressure on the interest rates of developed economies. Export-driven economic growth in emerging countries has generated substantial amounts of surpluses in countries that have boosted the global supply of savings. Moreover, rising inequality and insufficient social protection have led to an increased propensity to save. On the demand side, factors such as population ageing, debt deleveraging and decreased capital goods prices have pushed demand for loanable funds down. This, together with an increase in global saving supply and the tendency to shift investment towards safety assets – observed since the end of the 2009 recession – has shifted the saving-investment balance upward and led to a permanent decline in interest rates.

The term ‘secular stagnation’ was initially invented by the American economist Alvin Hansen in the late 1930s in an attempt to explain the languid growth of the US economy in the first years after the Great Depression. The increase in government spending had softened the freefall, but growth was still sluggish. According to Hansen, the engines of economic progress in the nineteenth century were no longer available. Technological progress triggered by the inventions of the Industrial Revolution had lost momentum and working age population growth had slowed considerably. Moreover, that period witnessed a massive deleveraging process and private companies were more inclined to repay debt than to invest in new projects. All these harmed aggregate demand and led to a period of low growth that looked permanent. However, the increase in military spending during the Second World War, the baby boom in the Unites States and the increase in female participation in the labour market proved Hansen's theory wrong.

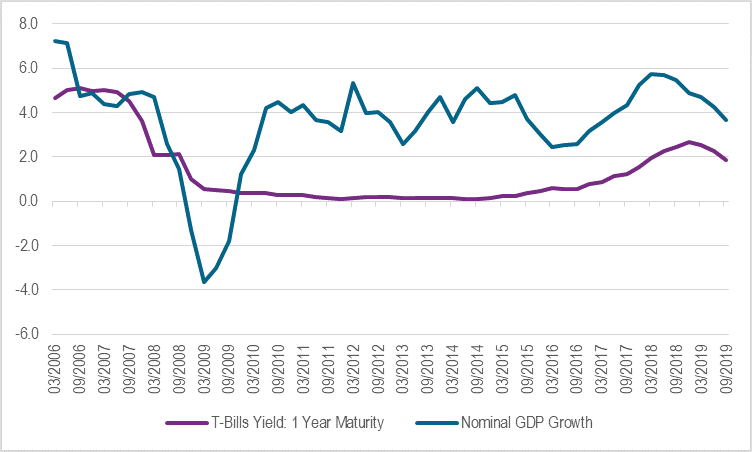

However, the economic condition of the advanced economies in the post-crisis decade looks a lot like that of the late 1930s, and to a certain extent that of Japan in the early 1990s. Population growth is decelerating to near-zero levels, the share of the working-age population is constantly decreasing and the developed economies, as well as the major emerging ones, are undergoing further deleveraging. Since the economic stagnation of the 1930s, the importance of government spending to boost growth has become common sense for policy-makers in developed economies. This has made the consequences of the 2009 recession much softer than they could have been, especially in the US, while the austerity experiment in Europe resulted in a double-dip recession in 2011. Moreover, in a deleveraging period, the increase in government debt to a certain limit has a positive effect not only on growth, but also on indebtedness. In October 2019 (the latest data available) the interest rate on US treasury bills with one-year maturity was 1.6%, far below nominal GDP growth (chart 3). In other words, a unit of government debt-driven growth actually reduces the overall debt-to-GDP ratio.

US Treasury Bills Yield and Nominal GDP Growth

Source: The Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Board, CEIC

Growth driven by government debt is not a policy that can last forever. In the long-term, just like in Hansen's era, the key to reboot economic progress is to restore investment outlets. An ageing population is hard to reverse, so technological progress remains the only sustainable growth engine. However, the post-crisis period of 2009-2018 was another decade of productivity growth slowdown. According to OECD data, in that period the annual growth of GDP per hour worked in the United States decelerated to an average of 2.6% from 4.5% in 1999-2008 and 4% in 1989-1998. In 2013, the British economist Robert Gordon estimated that the total factor productivity (TFP) growth in 2004-2014 had decelerated to 0.54% from 1.43% in 1996-2004. The figures for the other industrialised economies are even more worrisome, proving that both hypotheses for demand- and supply-side secular stagnation are solid enough to explain the current economic condition of the advanced economies.

The trade and currency wars that we are witnessing today are not new – they have occurred in every deleveraging period in modern history. But while they may have some short-term positive effects for certain economies, it is a zero-sum game for the global economy as a whole. Fiscal policy is a necessary tool to overcome demand-side challenges in the short-term, but without substantial acceleration of value-added innovations, radical enough to boost productivity growth, the undergoing technological revolution will not be enough to prevent another decade of stagnation.

To see the full article, along with other key pieces surrounding 'new economy' industries, download the Foresight 2020 report for free here.

.png?width=160&name=ceic-logo-Vector%20logo%20no%20tagline%20(002).png)

.png)