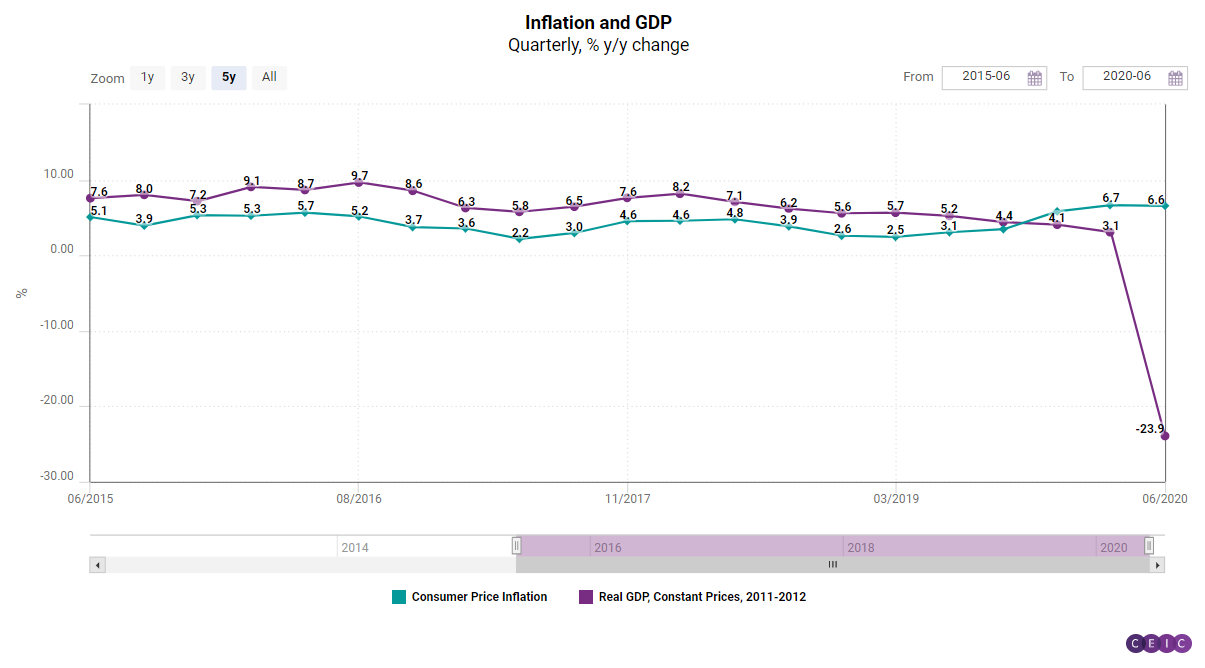

Over the years, India’s GDP has been through the usual crests and troughs, but the pandemic has plunged it to a 23.9% y/y decline in Q2 2020, the sharpest drop in the history of the nation.

However, India had been experiencing a slowdown in GDP growth since Q2 2018, primarily as a result of deteriorating domestic demand. To add to the woes, India has seen a sustained increase in y/y headline inflation since January 2019. This can essentially lead to a stagflation-like situation in India, marked by low GDP growth and high inflation. The last two decades have shown that the volatility of the inflation rate can be a serious threat to economic growth momentum. India’s annual CPI grew from 3.8% in 2001 to almost 12.0% in 2010, post the global financial crisis, and dropped back to 3.7% y/y in 2019. The double-digit growth in inflation forced the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to adopt the concept of “inflation-targeting” in its monetary policy.

Prior to the introduction of CPI as the main measure of inflation in India in 2009, the movement of prices in the country was primarily measured by the wholesale price index (WPI). The WPI was also used by the RBI in the formulation of the monetary policy, following the monetary targeting framework and the multiple indicator approach (MIA). Another key usage of the WPI before 2009 was in the calculation of the GDP deflator at current prices, which was further used to calculate the GDP at constant prices. After 2009 though, the CPI replaced the WPI as a primary measure of price movement in India mainly due to the change of the approach to the formulation of the monetary policy in India from MIA to a revised flexible inflation targeting (FIT). This change was made so that the RBI could achieve better price stability.

Inflation Vs. Growth

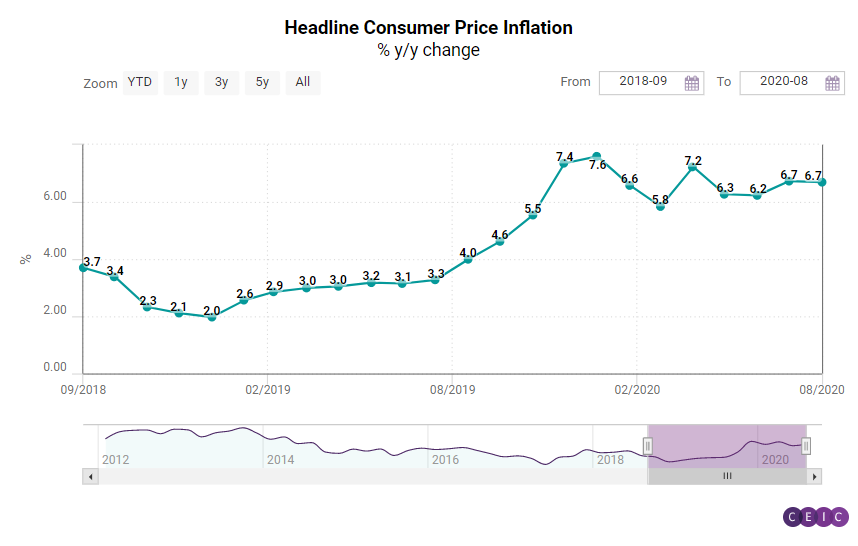

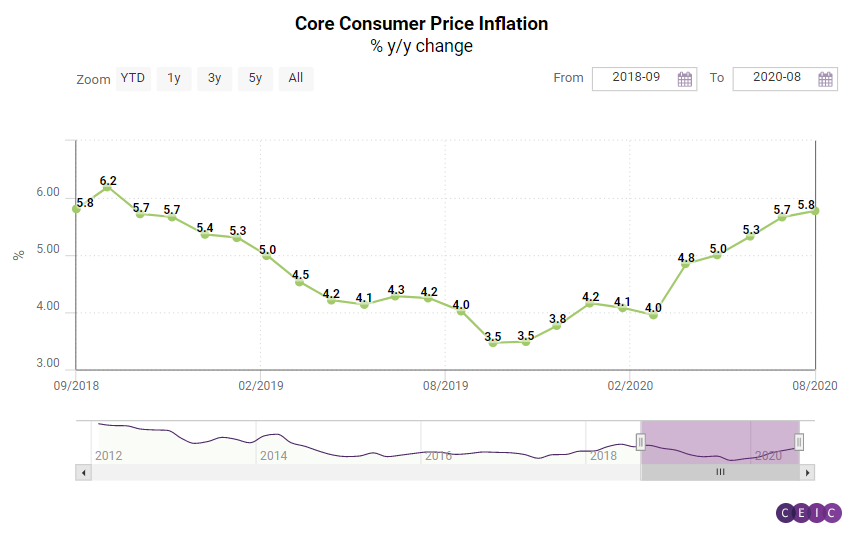

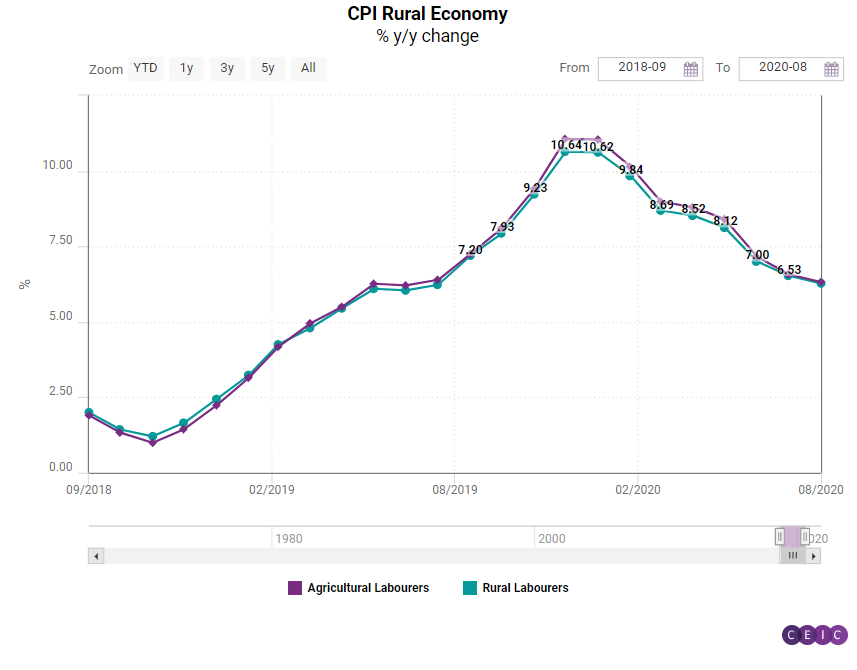

Inflation can be further differentiated into headline and core inflation, the former being more volatile, taking food and fuel prices into account, while the latter being more stable, capturing any increase in other items pointing to underlying changes in consumer patterns. Food and fuel are the usual suspects in case of any increase in headline inflation. Due to seasonality, there are substantial fluctuations in the prices of different staple consumer goods that are part of the Indian CPI basket such as different pulses and grains, milk, fruit, and vegetables. In many cases, the CPI pertaining to rural workers and agricultural workers can help understand an increase in overall inflation, reflecting the change of the purchasing power of goods in the CPI basket. The monetary and fiscal responses of the Indian government to the different crises in the past and also with regard to the current COVID-19 situation can trigger an increase in inflation. While there has been some improvement over the years, there is still considerable uncertainty and unwanted fluctuation in inflation.

While the annual y/y CPI figures have improved considerably since the peak in 2010, 2019 and 2020 have proven to be a real challenge for the stability of the inflation and economic growth in India. In January 2019, the inflation in India hit a new low since the beginning of the century, at 1.97% y/y. This brought about a sense of optimism for the future development of the economy but was ultimately short-lived. The following months saw almost steady growth in inflation, caused primarily by rising food prices. The result of this was a peak of the CPI to 7.59% in January 2020 and it has continued to gravitate around this level ever since.

On the other side, India's real GDP has shown a steep decline since Q1 2020, which is likely to damage the business environment, and ripple through the economy in the form of higher unemployment, lower-income, and lower demand. Furthermore, there is also a great apprehension about the negative effect it might have on the informal sector in India, which not only serves as the backbone of the Indian economy but is also the most vulnerable to slowdowns and recessions. Between FY2019 and FY2020, the y/y GDP growth fell from 6.1% to 4.2% and the prognosis is not in favor of recovery as a result of the COVID-19 crisis and its accompanying lockdowns both in India and around the world. That in mind, the quarterly trend in the observations of the y/y GDP growth in India from Q2 2018 onward shows a similar pattern, reflecting the current crisis situation, falling from 3.1% in Q1 2020 to a staggering -23.9% in Q2 2020. While many of these troubling numbers are likely to undergo certain revisions in the following weeks as there have been disruptions in the data collection processes, the final figures are not expected to stray far from the initial shocking results.

These figures showcase the Indian economy's sharpest decline since the country first started releasing its quarterly GDP in 1996. According to many economists and experts, this unprecedented decline not only sets back India's economic progress by years but is also a sure sign of the start of a heavy recession. Still, as this is only the first quarter since the beginning of the crisis that showed such a dramatic drop in economic growth, should India manage to mitigate that in the third quarter of 2020 at least slightly, there might still be hope of evading the most pessimistic scenario. Many high-frequency indicators of economic activity such as industrial production, automobile sales, and steel production are already showing improvement since the strict lockdown was lifted. The optimistic expectations for recovery of the Indian economy suggest a possible reach into positive numbers sometime in late 2020 or early 2021. However, this prognosis relies heavily on the sustained improvement in economic activity and more specifically, on the recovery of both local and international demand for Indian-produced goods and services over the next three quarters of FY2021. This might prove to be easier said than done, considering the lack of slowdown in the new COVID-19 cases in the country and the need for strict measures for probably many months ahead, but should businesses manage to adapt and start operating at a higher capacity, there is a significantly better chance of recovery within the next year.

Impact of COVID-19

India has become the third most affected country by COVID-19 in the world following only the US and Brazil. Since the beginning of September 2020, the daily increase in confirmed COVID-19 cases in India has hit the 80,000 mark and only keeps rising. The total cases have already exceeded 4mn people of whom almost 70,000 have lost their lives. The continuous rise in the number of cases has created severe disruptions in the supply chains of many industries dependent on domestic and foreign suppliers, which in turn, are affecting the economic activity in India. In terms of inflation, CPI has been growing ever since it hit 1.97% y/y in January 2019. In 2020 inflation remained above the 6% upper target band set forth by the RBI in December 2019.

The increase in CPI inflation is driven primarily by the growing food and beverage prices, followed by an increase in prices of miscellaneous items, and to some extent by an increase in the pan, tobacco, and intoxicant prices. Looking at the CPI basket of staple items in India, the monthly figures provided by the Central Statistics Office show that food prices, which account for almost half of the entire inflation basket, have been exerting significant upward pressure on inflation since the peak of the crisis in April 2020. This increase in headline inflation can be primarily attributed to the accelerated growth in vegetable prices, from 2.8% y/y in July 2019 to 60.50% y/y in December 2019, caused by heavy unseasonal rains.

In April 2020, the headline inflation increased to 7.2% y/y, driven largely by an increase in the prices of pulses and vegetables. In May 2020, the prices of meat and fish soared and put additional pressure on inflation. The latest figures for August 2020 show a slight moderation in food and beverage prices, barring the prices of vegetables and milk that continue to increase, by 11.41% y/y and 4.02% y/y, respectively.

While there has been some downward pressure coming from the prices of certain items on the basket such as wheat, garlic, onion, coconut, lemon, mango and a few others, they are still not enough to offset the already heavy upward pressure on the CPI from the rest of the items which show a more significant price increase. This can be mainly explained by the disruptions in the supply chain in many industries and economic activities. The Central Government of India has started to slowly and cautiously ease the imposed restrictions in order to minimize future disruptions in some areas of the country but the still active regional lockdowns, especially in many of the more important agricultural states in India such as West Bengal (rice, vegetables), Uttar Pradesh (sugarcane, wheat), Gujarat (cotton, groundnut), Assam (tea) and Madhya Pradesh (pulses such as soybean and garlic) have had a serious impact on harvesting and yields. Even with the initial opportunity for a good harvest in April, producers were not able to distribute their output due to transport restrictions and businesses closing down, which left the harvested production unused and in need of immediate storage. In many cases, producers extended the longevity of their products in order to enable deferred sales but it came at the cost of increased prices. An example of that is milk, where a large part of the unsold volume was converted to skimmed milk powder and butter in order to make it last longer and then stored accordingly.

The Central Bank and the Monetary Policy

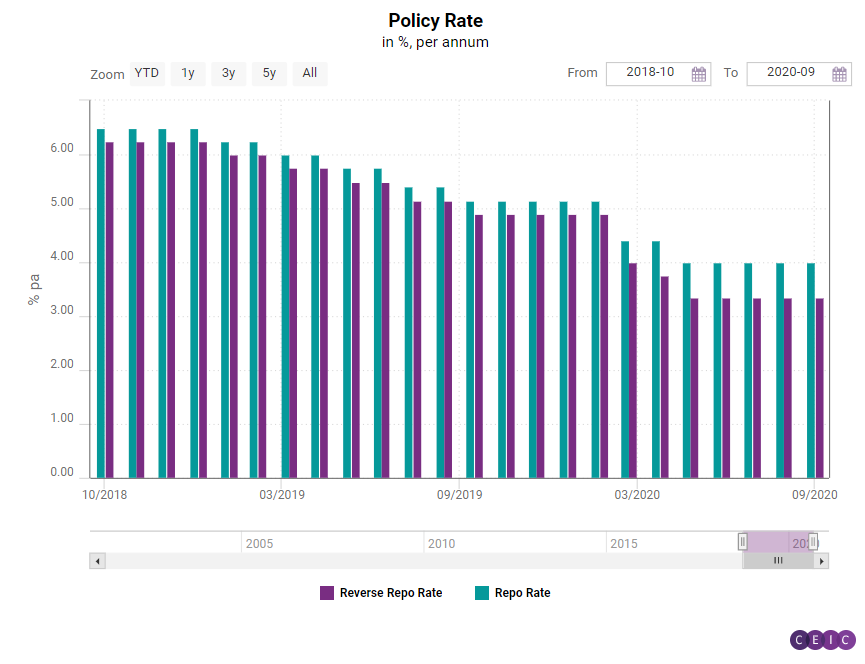

Since the beginning of the crisis, the RBI has been under a lot of pressure to exercise its policy and regulatory tools to aid the recovery of India's economy. One such key role of the RBI was to ensure ample liquidity in the financial system, and it has done so by means of security purchasing, transfers of billions of US dollars to the government, as well by providing more space and safety for lenders to purchase and hold government bonds without experiencing losses because of possible price volatility. Since March 2020, the RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has slashed the repo rate by a total of 115 bps and the reverse repo rate by 155 bps, in accordance with the already adopted accommodative policy stance of the central bank. Since the RBI follows a twin mandate of increasing GDP growth while maintaining inflation within the target band, multiple rate cuts were essential to help buffer the demand and supply shock that resulted from the lockdown. However, the sustained inflation has become an obstacle in the way of rate cuts and the MPC has withheld any rate cut at the August 2020 meeting, despite continuing their accommodative stance.

Easing monetary policy alongside a considerable fiscal stimulus is marked by some degree of peril. The stimulus is expected to boost demand thanks to greater purchasing power in the hands of the people, but its effect on output is unlikely to be positive if not matched with increased productivity. Furthermore, household inflation expectations may be readjusted upwards, which would lead businesses to estimate an increase in costs and lay off employees, which in turn would lead to a further fall in output. In this context, India’s GDP slowdown prior to the COVID-19 crisis raises questions about the country’s economic stability, and more importantly, if the fiscal stimulus can positively impact output. However, the pandemic has compelled the Indian government to implement a slew of measures, several of which are long-term amendments. Proposed amendments in regulations, development of required infrastructure, and easing of investment norms across sectors with a focused push to Make in India would help grow businesses and employment. Otherwise, simply increasing public spending can spur stagflation, putting the economy in greater difficulty.

It is interesting to note the power of household inflation expectations in driving an economy towards high inflation, or even a recession. Hence, the central bank takes cognizance of this data while forming policy. The quarterly Inflation Expectation Survey of Households (IESH) conducted by the RBI reveals inflation expectations of urban households from 18 cities across the country. While IESH holds substantial differences with actual inflation, it does reveal that people foresee an increase in inflation in the near future. This notion is also supported by the findings of the Professional Forecaster’s Survey (PFS), also conducted by the RBI. This is definitely a worrisome trend, in light of the fiscal stimulus and falling GDP, but a recovery in high-frequency economic indicators offers hope for the economy.

Recovery of the economic growth and the inflation rate in India is strongly dependent on the speed of the measures taken by the national government of India as well as the global attempts to contain the spread of the virus and create a vaccine. The monetary and liquidity measures taken by the RBI as well as the fiscal measures introduced by the government could help in managing the impact the crisis has had on the domestic demand and also aid in the recovery of the private sector economic activity, which has suffered significant damage due to the crisis and its accompanying restrictive measures, but the actual results will take time to show which might lead to continuous great losses for many businesses. Ultimately, this would have a reflection on the economy as a whole.

Sign in to read the full data analysis here. Alternatively, download the latest, comprehensive analysis of India's economy with the CEIC India Economy in a Snapshot Q3 2020 Report.

.png?width=160&name=ceic-logo-Vector%20logo%20no%20tagline%20(002).png)