As China is the first country to start recovering from the COVID-19 outbreak, all eyes are on the Asian giant again, this time looking for lessons and hope. More and more countries are adopting China’s approach to build new or transform existing facilities into temporary hospitals – a niche of the construction industry that has lots of potential not only in times of crisis.

Media worldwide are constantly circulating grim footage of helpless patients supported by life-saving equipment and exhausted medical workers in full protective gear fighting the invisible killer. Against this backdrop, videos showing Chinese workers building a temporary hospital for COVID-19 patients in the worst-hit city of Wuhan captured the attention of hundreds of millions of viewers seeking reassurance that swift measures are possible and applicable at such critical times.

With mesmerising efficiency and perfect co-ordination the dozens of construction machines and thousands of workers built something that would normally take months in a matter of days. And, equally importantly during times of crisis, it did not cost a fortune.

Prepare for the worst

The message of healthcare institutions everywhere has been the same – the COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbated by the insufficient capacity of the intensive care units which will soon be or already are overwhelmed by the rising number of patients who require treatment at a hospital. The World Health Organization (WHO) advised health authorities to assess the readiness and capacity of the existing facilities to provide basic emergency care for seriously ill patients, to set screening protocols, to ensure the laboratory testing of patients and other related requirements that prove vital in the fight against the new coronavirus.

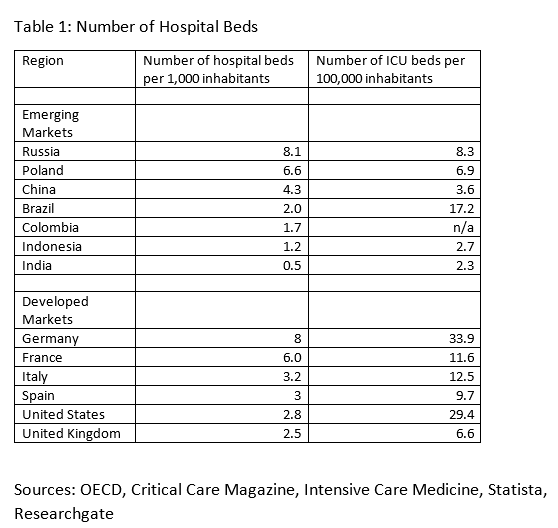

A comparison of hospital capacities between the countries is not telling even if we focus on specific groups, such as emerging markets.

Countries have organised their healthcare systems differently depending on their population numbers, density and territorial distribution. However, what has been working so far might no longer be adequate. The arrival of a pandemic requires a substantially different approach that almost no one seems to be ready for.

The possible COVID-19 complications require the immediate hospital admission of some patients. They take up hospital beds, leaving no room for other patients, either with or without COVID-19, who still have to receive hospital treatment. There is also the need for isolated testing and patient care facilities so as not to threaten the general operations of hospitals and laboratories. So, in order to be able to abate public fears of COVID-19 intra-hospital transmission and still provide immediate patient care, countries had to resort to ad hoc measures.

In record time

China was the first country to start building temporary hospitals during the pandemic. Realising the public health threat posed by the surging numbers of COVID-19 patients, the authorities approved the transformation of stadiums, conference centres, and even classrooms into makeshift hospitals in Wuhan. The shortage of hospital beds in the city changed the protocol for admission of patients.

Suspicious patients were tested and admitted into the temporary hospitals, while those developing or already having severe symptoms were moved to general hospitals, where ICU beds and mechanical ventilation could be used if necessary. The authorities were very strict about one thing though – regardless of the need for quick availability of such makeshift hospitals, there was no room for compromise about the containment of the infection within these facilities.

In addition to converting existing buildings, the authorities also ordered the construction of two hospitals that were both launched in early February. China had previous experience with the 2003 SARS crisis, during which the Beijing Xiaotangshan Hospital was built. The Wuhan Huoshenshan Hospital (1,000 beds) and Leishenshan Hospital (1,500 beds) were both erected in a matter of days and, like the Beijing SARS hospitals, were made with prefabricated elements. These measures allowed Wuhan to substantially enhance admission capacities for COVID-19 patients in separate facilities, while allowing general hospitals to continue their regular operations and minimising the threat of virus transmission.

Such emergency measures do not come without their own set of challenges. In this case, they range from engaging local authorities, architects and builders, dealing with infrastructure, logistics and supply, to finding staff and medical equipment, supplies and gear in order to ensure the safety of both patients and medical personnel.

Do you copy?

While China is already on the road to recovery, the coronavirus has spread globally and new hot spots have formed. Different healthcare systems mean that each country is facing different challenges and can spare different budgets to deal with them. The emerging markets have been singled out as places where poorer overall healthcare means that more people already have pre-existing health conditions which would make the coronavirus more deadly. The expected high numbers of COVID-19 patients mean that hospitals would be swamped and would probably fail to provide proper care to all patients – a bleak scenario that is also confirmed by the lower numbers of ICU beds in these countries in comparison to developed markets.

This is why a growing number of countries, both in the developing and in the developed world, are resorting to the cheaper alternative of makeshift hospitals in order to alleviate some of the pressure that healthcare facilities are about to face.

Developing countries have taken different approaches to tackling this problem. Some are building new hospitals. Brazil’s BRL 140mn Fiocruz Hospital Center with 200 beds in Rio de Janeiro should be ready in two months. A hospital with 500 beds and separate dormitories for 1,000 staff in Golokhvastovo, near the Russian capital Moscow, should be ready in a month, and Kazakhstan is building a 280-bed hospital in Almaty. Armenia is working on a smaller scale, taking just 3-4 days to add a new hospital ward with 40 isolation rooms with one bed each.

Existing buildings are being transformed in Medellin, Colombia, where an abandoned hospital is being renovated. Serbia plans to reconstruct an existing facility into a new hospital with 70 beds in 17 days and to turn the Belgrade Fair into a makeshift hospital. In Indonesia’s capital Jakarta, the Kemayoran Athletes Village is being transformed into a temporary hospital.

Medical tents are pitched on the parking lot of the Military Hospital in Colombia’s capital Bogota, and in several cities in Poland, while Vietnam has set up a makeshift rapid testing centre near the Bach Mai hospital in Hanoi.

In sickness and in health

The scale of the pandemic means that in most cases the governments will pay for the construction or conversion of temporary hospitals. There are some exceptions though - the Belgrade hospital reconstruction is funded by local engineering company Termomont, while in India domestic behemoth Tata Group and the state are working together to build a hospital in Kasaragod district, which will have 540 isolation beds and a quarantine facility for 450.

But companies, too, are seeking commercial opportunities. As the situation in China is now slowly returning back to normal, local daily Global Times quoted a China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC) Limited official as saying that an offer has been made to construct makeshift hospitals in India such as those it built in Wuhan. The company has already completed a 100-bed temporary hospital in Trinidad and Tobago in just 12 days. Such services, originally necessitated by the pandemic, can become applicable under many different circumstances where fast action is required to address specific needs.

The biggest advantage of such quick construction or transformation projects is that the ready facilities can be put into use immediately and at a much lower cost. These facilities do not have to be permanent and would allow for the quick deployment of experts, employees or mobile units or for the early launch of operations before facilities of a more permanent nature are being built. Since the construction of temporary buildings is often done with prefabricated elements, they can be disassembled and reassembled multiple times and on different locations.

During the pandemic governments can resort to using state resources and even the army, as well as avoid bureaucracy - a luxury that construction companies will not have. They must cope with limited resources, regulatory policy issues, and red tape. They will also face obstacles such as the need to construct the necessary adjacent infrastructure. There will also be project-specific challenges such as the need to mobilise resources for such projects or the underlying limitations of prefabrication.

Emerging markets are to an extent undiscovered frontiers where money is tight, but opportunities are vast. Being able to quickly build facilities at a fraction of the normal cost means that the entry of more companies including locally-based ones will become more affordable. While developed countries have the experience and the budgets to build temporary hospitals, the emerging markets are now facing the challenge, but also the opportunity to learn quickly how to do that. This might be a valuable lesson that the developing world will take from these hard times.

Access the latest news, data and analysis with the CEIC COVID-19 Outbreak and Impact Monitor.

.png?width=160&name=ceic-logo-Vector%20logo%20no%20tagline%20(002).png)