As early as mid-March 2020, the Central Bank of Brazil announced a package of measures aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The measures were to increase the liquidity of the financial system by BRL 1.2tn to ensure that financial institutions can provide a sufficient amount of liquidity to firms and individuals. In addition, the central bank announced temporary capital relief for financial institutions, which would potentially result in an expansion of the credit supply by BRL 1.16tn. Other measures included a reduction in the reserve requirement ratio to 17% from 25%, a Temporary Liquidity Line in domestic currency to financial institutions, and more flexible regulation on overhedging operations of investments abroad, to name but a few.

In addition to the emergency measures, the central bank cut the Selic rate (the main policy rate) by a cumulative 250 bp throughout 2020. This has left the Selic rate at a historic low of 2% in August and September 2020, coupled with a forward guidance, under which the central bank committed to avoid rate hikes in the foreseeable future. According to the Monetary Policy Committee, the room for further easing is small due to prudential and financial stability reasons.

As a consequence of the timely intervention, the central bank achieved several of its objectives. Inflation returned within the 2.5%-5.5% target range. Growth of lending to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and large non-financial companies accelerated significantly following the liquidity measures and averaged 15.9% and 16.1%, respectively, in the July-August period. Borrowing costs to both households and firms decreased: interest rates for individuals dropped to 24% in August, while rates for companies declined to 10.8%.

The liquidity measures might have softened the negative impact of COVID-19 on Brazilian equity prices. The benchmark stock market index Bovespa plummeted by 46.4% ytd in the height of the market turmoil on March 23, 2020. Following the large liquidity packages on behalf of the Central Bank of Brazil and other major monetary institutions worldwide, the Bovespa gained 48.8% from its trough by the end of Q3, with the major part of the gain achieved during Q2. As of the end of Q3 2020, the index was still 20% lower compared to the beginning of 2020.

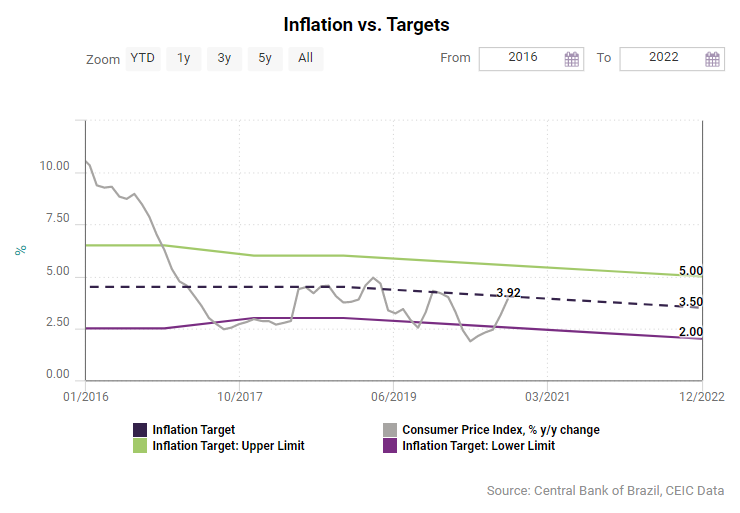

According to the October 2020 World Economic Outlook published by the IMF, inflation in Brazil is expected to average 2.7% in 2020 and 2.9% in 2021. This figure falls slightly short of the central bank’s target of 3% for 2020 but is within the desired range. This projection is made under the assumption that Brazilian GDP will contract by 5.8% in 2020 and grow by 2.8% in 2021. According to the Monetary Policy Committee’s projection from September 2020, inflation will average 2.1% in 2020, 3% in 2021 and 3.8% in 2022.

Impact on Credit

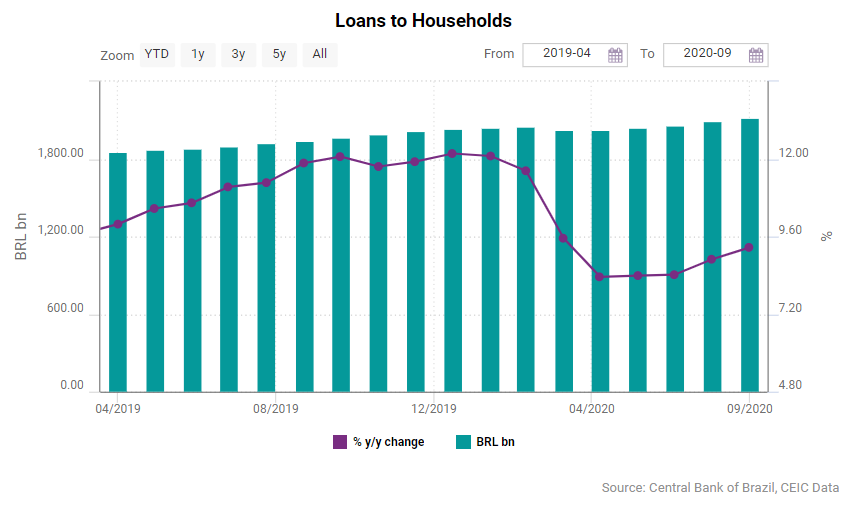

The Central Bank of Brazil’s accommodative monetary policy has been sweeping rapidly through the economy following the implementation of liquidity measures in mid-March. The magnitude of borrowing, however, has been distributed rather unevenly across market participants. Data shows that firms, especially large ones, have been quicker to make use of the lending facilities designed by the central bank. Loans to non-financial companies expanded by 15.1% y/y and 16/7% y/y in July and August, respectively. The growth of lending to large non-financial companies accelerated since March, i.e. the month that the central bank announced the liquidity measures. Given their large financial and accounting departments, these companies are in a better position to make use of the central bank’s facilities. Lending to large non-financial companies expanded by an average 12.2% y/y in Q2 2020 and by 15.9% y/y on average in the first two months of Q3 2020. In contrast, the growth of loans to SMEs remained below 9% throughout Q2 but rapidly accelerated in Q3 to average 16.12% y/y over the July-August period.

The central bank’s easing does not seem to have had a significant effect on household borrowing. Following an acceleration of lending to households over 2019, the uncertainty around the COVID-19 crisis seems to have deterred households from borrowing and lending growth averaged 8.6% y/y over the July-August period. An important additional factor is the marginal decline of the rates at which households can borrow from commercial banks. The low creditworthiness of Brazilian households is a major reason for the high rates which banks offer despite the record low Selic rate. In addition, according to estimates, nearly a third of the Brazilian population is unbanked and does not have access to credit nor debit cards, hence a direct transmission of monetary policy to households is difficult to achieve.

Impact on Inflation

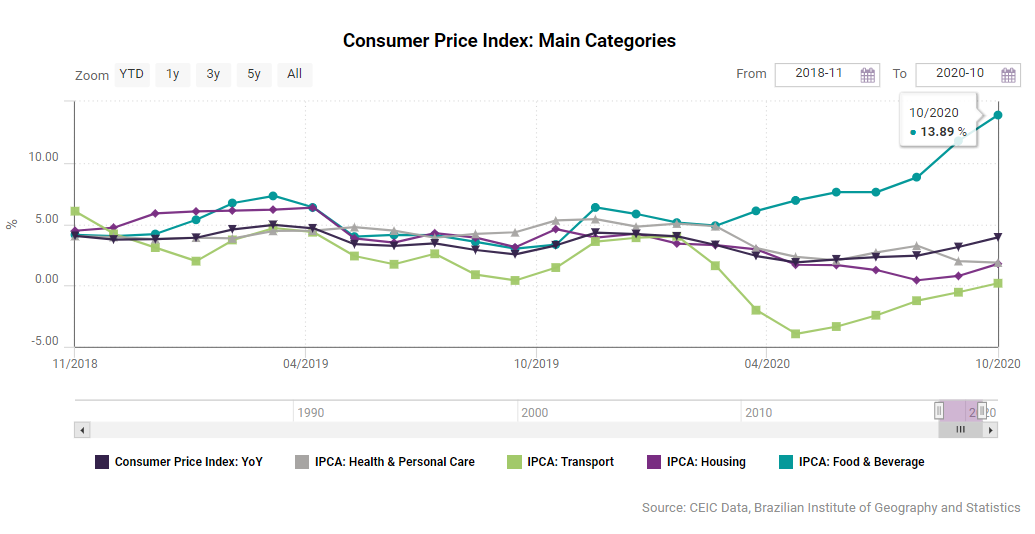

The liquidity measures provided by the central bank were slow to affect inflation, as it did not return within the desired range until September 2020. Despite the unprecedented liquidity injection, inflation declined to 1.88% in May – significantly below the 2.5% lower bound of the central bank’s target. Although inflation of food and beverages, which bears the largest weight of the CPI, rose to 6.9% in May from 4.9% in March, the effect was outweighed by a 3.9% decline of transportation prices in May. In addition, inflation in housing also declined to 1.7% in May from 3.29% in March 2020.

However, inflation trended upwards since June to reach 3.15% in September, closing in to the target of 4% set by the monetary policy authority. The rise was driven by an increase of food and beverages inflation to 11.8%. Such a high food inflation was last recorded in Q4 2016 while Brazil was in the middle of a presidential impeachment process and still in the trap of a severe economic recession. The rise in inflation of food items will likely constrain the possibility for a further reduction of the Selic rate or expansion of the liquidity facilities.

A potential further rise in inflation will be especially detrimental to household savings in deposits and cash. Given the 3.14% inflation and the Selic rate at 2% as of September 2020, it means that effectively households are getting a significant negative return on their deposits. Hence, the Central Bank of Brazil will have the task to strike the delicate balance between stimulating the economy with lower rates, on the one hand, and preserving people’s savings, on the other.

Money supply grew exponentially due to the liquidity facilities created by the central bank in mid-March 2020. The growth of M1 – a measure which includes all cash and check deposits in the economy – surpassed significantly that of M2, which also includes assets easily convertible to cash. The growth of M1 accelerated from 15.5% in March to 45.9% in August 2020, while that of M2 rose from 13.5% to 28.5% in the same period. A driver behind that was an increased money printing for the distribution of social aid payments to the households most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since a large proportion of the Brazilian population remains unbanked, people were queuing in front of the banks to receive this vital help. As a fraction of GDP, the monetary base rose to 5.6% in August from 4.19% in March 2020. The money supply measure M1 reached 7.6% of GDP in August, while M2 rose to 51.9%. International reserves declined sharply by 10.7% y/y in April. Although they recovered slightly since then, reserves were still down 8.1% y/y in August 2020.

The value of the central bank’s total assets rose to a record high BRL 4.05tn in June 2020 from BRL 3.4tn at the end of 2019. The total value of assets fluctuated in the following two months, rising by 12.9% y/y to BRL 4.01tn in August. The increase was driven by purchases of both domestic and foreign currency denominated securities. The holdings of foreign securities increased by 17.4% y/y to BRL 1.7trn in August, while those of federal government securities rose by 3.3% y/y to BRL 1.87trn. The liquidity facilities created by the central banks seem to have ensured higher financial stability. The banking sector’s Tier 1 capital ratio, which measures a bank’s tier 1 capital relative to its total risk-weighted assets, fell to 13.16% in March 2020. Following the liquidity measures, the Tier 1 ratio rose to 14.2% in July 2020. After rising throughout 2019, banks’ return on assets declined to 1.57% from 2% between January and June 2020...

Sign in to read the full data analysis here. You may also be interested in downloading the latest, comprehensive analysis of Brazil's economy with the CEIC Brazil Economy in a Snapshot Q3 2020 Report.

.png?width=160&name=ceic-logo-Vector%20logo%20no%20tagline%20(002).png)